This is the third of the three-part series on the topic of TFIDF in libraries. In Part I the why’s and wherefore’s of TFIDF were outlined. In Part II TFIDF subroutines and programs written in Perl were used to demonstrate how search results can be sorted by relevance and automatic classification can be done. In this last part a few more subroutines and a couple more programs are presented which: 1) weigh search results given an underlying set of themes, and 2) determine similarity between files in a corpus. A distribution including the library of subroutines, Perl scripts, and sample data are available online.

Big Names and Great Ideas

As an intellectual humanist, I have always been interested in “great” ideas. In fact, one of the reasons I became I librarian was because of the profundity of ideas physically located libraries. Manifested in books, libraries are chock full of ideas. Truth. Beauty. Love. Courage. Art. Science. Justice. Etc. As the same time, it is important to understand that books are not source of ideas, nor are they the true source of data, information, knowledge, or wisdom. Instead, people are the real sources of these things. Consequently, I have also always been interested in “big names” too. Plato. Aristotle. Shakespeare. Milton. Newton. Copernicus. And so on.

As a librarian and a liberal artist (all puns intended) I recognize many of these “big names” and “great ideas” are represented in a set of books called the Great Books of the Western World. I then ask myself, “Is there someway I can use my skills as a librarian to help support other people’s understanding and perception of the human condition?” The simple answer is to collection, organize, preserve, and disseminate the things — books — manifesting great ideas and big names. This is a lot what my Alex Catalogue of Electronic Texts is all about. On the other hand, a better answer to my question is to apply and exploit the tools and processes of librarianship to ultimately “save the time of the reader”. This is where the use of computers, computer technology, and TFIDF come into play.

Part II of this series demonstrated how to weigh search results based on the relevancy ranked score of a search term. But what if you were keenly interested in “big names” and “great ideas” as they related to a search term? What if you wanted to know about librarianship and how it related to some of these themes? What if you wanted to learn about the essence of sculpture and how it may (or may not) represent some of the core concepts of Western civilization? To answer such questions a person would have to search for terms like sculpture or three-dimensional works of art in addition to all the words representing the “big names” and “great ideas”. Such a process would be laborious to enter by hand, but trivial with the use of a computer.

Here’s a potential solution. Create a list of “big names” and “great ideas” by copying them from a place such as the Great Books of the Western World. Save the list much like you would save a stop word list. Allow a person to do a search. Calculate the relevancy ranking score for each search result. Loop through the list of names and ideas searching for each of them. Calculate their relevancey. Sum the weight of search terms with the weight of name/ideas terms. Return the weighted list. The result will be a relevancy ranked list reflecting not only the value of the search term but also the values of the names/ideas. This second set of values I call the Great Ideas Coefficient.

To implement this idea, the following subroutine, called great_ideas, was created. Given an index, a list of files, and a set of ideas, it loops through each file calculating the TFIDF score for each name/idea:

sub great_ideas {

my $index = shift;

my $files = shift;

my $ideas = shift;

my %coefficients = ();

# process each file

foreach $file ( @$files ) {

my $words = $$index{ $file };

my $coefficient = 0;

# process each big idea

foreach my $idea ( keys %$ideas ) {

# get n and t for tdidf

my $n = $$words{ $idea };

my $t = 0;

foreach my $word ( keys %$words ) { $t = $t + $$words{ $word } }

# calculate; sum all tfidf scores for all ideas

$coefficient = $coefficient + &tfidf( $n, $t, keys %$index, scalar @$files );

}

# assign the coefficient to the file

$coefficients{ $file } = $coefficient;

}

return \%coefficients;

}

A Perl script, ideas.pl, was then written taking advantage of the great_ideas subroutine. As described above, it applies the query to an index, calculates TFIDF for the search terms as well as the names/ideas, sums the results, and lists the results accordingly:

# define

use constant STOPWORDS => 'stopwords.inc';

use constant IDEAS => 'ideas.inc';

# use/require

use strict;

require 'subroutines.pl';

# get the input

my $q = lc( $ARGV[ 0 ] );

# index, sans stopwords

my %index = ();

foreach my $file ( &corpus ) { $index{ $file } = &index( $file, &slurp_words( STOPWORDS ) ) }

# search

my ( $hits, @files ) = &search( \%index, $q );

print "Your search found $hits hit(s)\n";

# rank

my $ranks = &rank( \%index, [ @files ], $q );

# calculate great idea coefficients

my $coefficients = &great_ideas( \%index, [ @files ], &slurp_words( IDEAS ) );

# combine ranks and coefficients

my %scores = ();

foreach ( keys %$ranks ) { $scores{ $_ } = $$ranks{ $_ } + $$coefficients{ $_ } }

# sort by score and display

foreach ( sort { $scores{ $b } <=> $scores{ $a } } keys %scores ) {

print "\t", $scores{ $_ }, "\t", $_, "\n"

}

Using the query tool described in Part II, a search for librarianship returns the following results:

$ ./search.pl books

Your search found 3 hit(s)

0.00206045818083232 librarianship.txt

0.000300606222548807 mississippi.txt

5.91505974210339e-05 hegel.txt

Using the new program, ideas.pl, the same set of results are returned but in a different order, an order reflecting the existence of “big ideas” and “great ideas” in the texts:

$ ./ideas.pl books

Your search found 3 hit(s)

0.101886904057731 hegel.txt

0.0420767249559441 librarianship.txt

0.0279062776599476 mississippi.txt

When it comes to books and “great” ideas, maybe I’d rather read hegel.txt as opposed to librarianship.txt. Hmmm…

Think of the great_ideas subroutine as embodying the opposite functionality as a stop word list. Instead of excluding the words in a given list from search results, use the words to skew search results in a particular direction.

The beauty of the the great_ideas subroutine is that anybody can create their own set of “big names” or “great ideas”. They could be from any topic. Biology. Mathematics. A particular subset of literature. Just as different sets of stop words are used in different domains, so can the application of a Great Ideas Coefficient.

Similarity between documents

TFIDF can be applied to the problem of finding more documents like this one.

The process of finding more documents like this is perennial. The problem is addressed in the field of traditional librarianship through the application of controlled vocabulary terms, author/title authority lists, the collocation of physical materials through the use of classification numbers, and bibliographic instruction as well as information literacy classes.

In the field of information retrieval, the problem is addressed through the application of mathematics. More specifically but simply stated, by plotting the TFIDF scores of two or more terms from a set of documents on a Cartesian plane it is possible to calculate the similarity between said documents by comparing the angle and length of the resulting vectors — a measure called “cosine similarity”. By extending the process to any number of documents and any number of dimensions it is relatively easy to find more documents like this one.

Suppose we have two documents: A and B. Suppose each document contains many words but those words were only science and art. Furthermore, suppose document A contains the word science 9 times and the word art 10 times. Given these values, we can plot the relationship between science and art on a graph, below. Document B can be plotted similarly supposing science occurs 6 times and the word art occurs 14 times. The resulting lines, beginning at the graph’s origin (O) to their end-points (A and B), are called “vectors” and they represent our documents on a Cartesian plane:

s |

c 9 | * A

i | *

e | *

n 6 | * * B

c | * *

e | * *

| * *

| * *

| * *

O-----------------------

10 14

art

Documents A and B represented as vectors

If the lines OA and OB were on top of each other and had the same length, then the documents would be considered equal — exactly similar. In other words, the smaller the angle AOB is as well as the smaller the difference between the length lines OA and OB the more likely the given documents are the same. Conversely, the greater the angle of AOB and the greater the difference of the lengths of lines OA and OB the more unlike the two documents.

This comparison is literally expressed as the inner (dot) product of the vectors divided by the product of the Euclidian magnitudes of the vectors. Mathematically, it is stated in the following form and is called “cosine similarity”:

( ( A.B ) / ( ||A|| * ||B|| ) )

Cosine similarity will return a value between 0 and 1. The closer the result is to 1 the more similar the vectors (documents) compare.

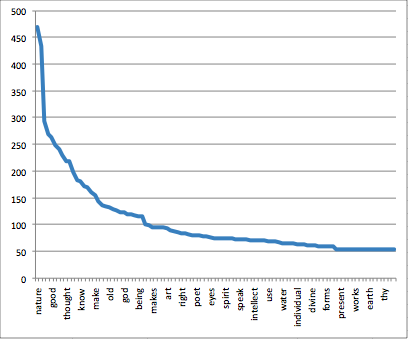

Most cosine similarity applications apply the comparison to every word in a document. Consequently each vector has a large number of dimensions making calculations time consuming. For the purposes of this series, I am only interested in the “big names” and “great ideas”, and since The Great Books of the Western World includes about 150 of such terms, the application of cosine similarity is simplified.

To implement cosine similarity in Perl three additional subroutines needed to be written. One to calculate the inner (dot) product of two vectors. Another was needed to calculate the Euclidian length of a vector. These subroutines are listed below:

sub dot {

# dot product = (a1*b1 + a2*b2 ... ) where a and b are equally sized arrays (vectors)

my $a = shift;

my $b = shift;

my $d = 0;

for ( my $i = 0; $i <= $#$a; $i++ ) { $d = $d + ( $$a[ $i ] * $$b[ $i ] ) }

return $d;

}

sub euclidian {

# Euclidian length = sqrt( a1^2 + a2^2 ... ) where a is an array (vector)

my $a = shift;

my $e = 0;

for ( my $i = 0; $i <= $#$a; $i++ ) { $e = $e + ( $$a[ $i ] * $$a[ $i ] ) }

return sqrt( $e );

}

The subroutine that does the actual comparison is listed below. Given a reference to an array of two books, stop words, and ideas, it indexes each book sans stop words, searches each book for a great idea, uses the resulting TFIDF score to build the vectors, and computes similarity:

sub compare {

my $books = shift;

my $stopwords = shift;

my $ideas = shift;

my %index = ();

my @a = ();

my @b = ();

# index

foreach my $book ( @$books ) { $index{ $book } = &index( $book, $stopwords ) }

# process each idea

foreach my $idea ( sort( keys( %$ideas ))) {

# search

my ( $hits, @files ) = &search( \%index, $idea );

# rank

my $ranks = &rank( \%index, [ @files ], $idea );

# build vectors, a & b

my $index = 0;

foreach my $file ( @$books ) {

if ( $index == 0 ) { push @a, $$ranks{ $file }}

elsif ( $index == 1 ) { push @b, $$ranks{ $file }}

$index++;

}

}

# compare; scores closer to 1 approach similarity

return ( cos( &dot( [ @a ], [ @b ] ) / ( &euclidian( [ @a ] ) * &euclidian( [ @b ] ))));

}

Finally, a script, compare.pl, was written glueing the whole thing together. It’s heart is listed here:

# compare each document...

for ( my $a = 0; $a <= $#corpus; $a++ ) {

print "\td", $a + 1;

# ...to every other document

for ( my $b = 0; $b <= $#corpus; $b++ ) {

# avoid redundant comparisons

if ( $b <= $a ) { print "\t - " }

# process next two documents

else {

# (re-)initialize

my @books = sort( $corpus[ $a ], $corpus[ $b ] );

# do the work; scores closer to 1000 approach similarity

print "\t", int(( &compare( [ @books ], $stopwords, $ideas )) * 1000 );

}

}

# next line

print "\n";

}

In a nutshell, compare.pl loops through each document in a corpus and compares it to every other document in the corpus while skipping duplicate comparisons. Remember, only the dimensions representing “big names” and “great ideas” are calculated. Finally, it displays a similarity score for each pair of documents. Scores are multiplied by 1000 to make them easier to read. Given the sample data from the distribution, the following matrix is produced:

$ ./compare.pl

Comparison: scores closer to 1000 approach similarity

d1 d2 d3 d4 d5 d6

d1 - 922 896 858 857 948

d2 - - 887 969 944 971

d3 - - - 951 954 964

d4 - - - - 768 905

d5 - - - - - 933

d6 - - - - - -

d1 = aristotle.txt

d2 = hegel.txt

d3 = kant.txt

d4 = librarianship.txt

d5 = mississippi.txt

d6 = plato.txt

From the matrix is it obvious that documents d2 (hegel.txt) and d6 (plato.txt) are the most similar since their score is the closest to 1000. This means the vectors representing these documents are closer to congruency than the other documents. Notice how all the documents are very close to 1000. This makes sense since all of the documents come from the Alex Catalogue and the Alex Catalogue documents are selected because of the “great idea-ness”. The documents should be similar. Notice which documents are the least similar: d4 (librarianship.txt) and d5 (mississippi.txt). The first is a history of librarianship. The second is a novel called Life on the Mississippi. Intuitively, we would expect this to be true; neither one of these documents are the topic of “great ideas”.

(Argg! Something is incorrect with my trigonometry. When I duplicate a document and run compare.pl the resulting cosine similarity value between the exact same documents is 540, not 1000. What am I doing wrong?)

Summary

This last part in the series demonstrated ways term frequency/inverse document frequency (TFIDF) can be applied to over-arching (or underlying) themes in a corpus of documents, specifically the “big names” and “great ideas” of Western civilization. It also demonstrated how TFIDF scores can be used to create vectors representing documents. These vectors can then be compared for similarity, and, by extension, the documents they represent can be compared for similarity.

The purpose of the entire series was to bring to light and take the magic out of a typical relevancy ranking algorithm. A distribution including all the source code and sample documents is available online. Use the distribution as a learning tool for your own explorations.

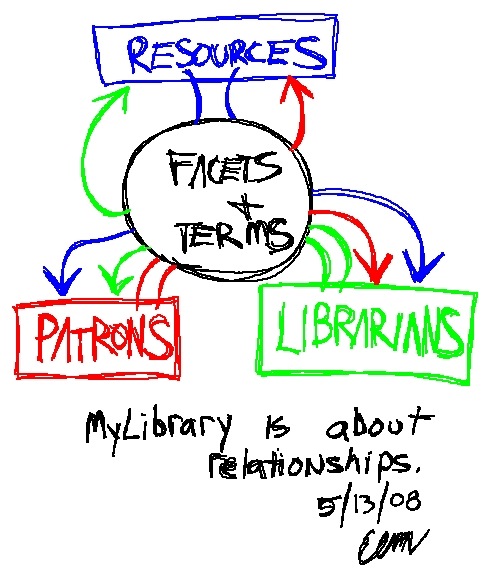

As alluded to previously, TFIDF is like any good folk song. It has many variations and applications. TFIDF is also like milled grain because it is a fundemental ingredient to many recipes. Some of these recipies are for bread, but some of them are for pies or just thickener. Librarians and libraries need to incorporate more mathematical methods into their processes. There needs to be a stronger marriage between the social characteristics of librarianship and the logic of mathematics. (Think arscience.) The application of TFIDF in libraries is just one example.

I don’t exactly know how or why Google sometimes creates nice little screen shots of Web home pages, but it created one for my

I don’t exactly know how or why Google sometimes creates nice little screen shots of Web home pages, but it created one for my

As a community, let’s establish the Code4Lib Open Source Software Award.

As a community, let’s establish the Code4Lib Open Source Software Award.

This posting documents my experience at the Code4Lib Conference in Providence, Rhode Island between February 23-26, 2009. To summarize my experiences, I went away with a better understanding of linked data, it is an honor to be a part of this growing and maturing community, and finally, this conference is yet another example of the how the number of opportunities for libraries exist if only you are to think more about the whats of librarianship as opposed to the hows.

This posting documents my experience at the Code4Lib Conference in Providence, Rhode Island between February 23-26, 2009. To summarize my experiences, I went away with a better understanding of linked data, it is an honor to be a part of this growing and maturing community, and finally, this conference is yet another example of the how the number of opportunities for libraries exist if only you are to think more about the whats of librarianship as opposed to the hows.

The

The

More specifically, I have created a tiny system for copying scanned materials locally, enhancing it with a word cloud, indexing it, and providing access to whole thing. There is how it works:

More specifically, I have created a tiny system for copying scanned materials locally, enhancing it with a word cloud, indexing it, and providing access to whole thing. There is how it works:

The

The  As you may or may not know,

As you may or may not know,