In this posting I present two quantitative methods for denoting the “greatness” of a text. Through this analysis I learned that Aristotle wrote the greatest book. Shakespeare wrote seven of the top ten books when it comes to love. And Aristophanes’s Peace is the most significant when it comes to war. Once calculated, this description – something I call the “Great Ideas Coefficient” – can be used as a benchmark to compare & contrast one text with another.

Research questions

In 1952 Robert Maynard Hutchins et al. compiled a set of books called the Great Books of the Western World. [1] Comprised of fifty-four volumes and more than a couple hundred individual works, it included writings from Homer to Darwin. The purpose of the set was to cultivate a person’s liberal arts education in the Western tradition. [2]

To create the set a process of “syntopical reading” was first done. [3]. (Syntopical reading is akin to the emerging idea of “distant reading” [4], and at the same time complementary to the more traditional “close reading”.) The result was an enumeration of 102 “Great Ideas” commonly debated throughout history. Through the syntopical reading process, through the enumeration of timeless themes, and after thorough discussion with fellow scholars, the set of Great Books was enumerated. As stated in the set’s introductory materials:

…but the great books posses them [the great ideas] for a considerable range of ideas, covering a variety of subject matters or disciplines; and among the great books the greatest are those with the greatest range of imaginative or intellectual content. [5]

Our research question is then, “How ‘great’ are the Great Books?” To what degree do they discuss the Great Ideas which apparently define their greatness? If such degrees can be measured, then which of the Great Books are greatest?

Great Ideas Coefficient defined

To measure the greatness of any text – something I call a Great Ideas Coefficient – I apply two methods of calculation. Both exploit the use of term frequency inverse document frequency (TFIDF).

TFIDF is a well-known method for calculating statistical relevance in the field of information retrieval (IR). [6] Query terms are supplied to a system and compared to the contents of an inverted index. Specifically, documents are returned from an IR system in a relevancy ranked order based on: 1) the ratio of query term occurrences and the size of the document multiplied by 2) the ratio of the number of documents in the corpus and the number of documents containing the query terms. Mathematically stated, TFIDF equals:

(c/t) * log(d/f)

where:

- c = number of times the query terms appear in a document

- t = total number of words in a document

- d = total number of documents in a corpus

- f = total number of documents containing the query terms

For example, suppose a corpus contains 100 documents. This is d. Suppose two of the documents contain a given query term (such as “love”). This is f. Suppose also the first document is 50 words long (t) and contains the word love once (c). Thus, the first document has a TFIDF score of 0.034:

(1/50) * log(100/2) = 0.0339

Where as, if the second document is 75 words long (t) and contains the word love twice (c), then the second document’s TFIDF score is 0.045:

(2/75) * log(100/2) = 0.0453

Thus, the second document is considered more relevant than the first, and by extension, the second document is probably more “about” love than the first. For our purposes relevance and “aboutness” are equated with “greatness”. Consequently, in this example, when it comes to the idea of love, the second document is “greater” than the first. To calculate our first Coefficient I sum all 102 Great Idea TFIDF scores for a given document, a statistic called the “overlap score measure”. [7] By comparing the resulting sums I can compare the greatness of the texts as well as examine correlations between Great Ideas. Since items selected for inclusion in the Great books also need to exemplify the “greatest range of imaginative or intellectual content”, I also produce a Coefficient based on a normalized mean for all 102 Great Ideas across the corpus.

Great Ideas Coefficient calculated

To calculate the Great Ideas Coefficient for each of the Great Books I used the following process:

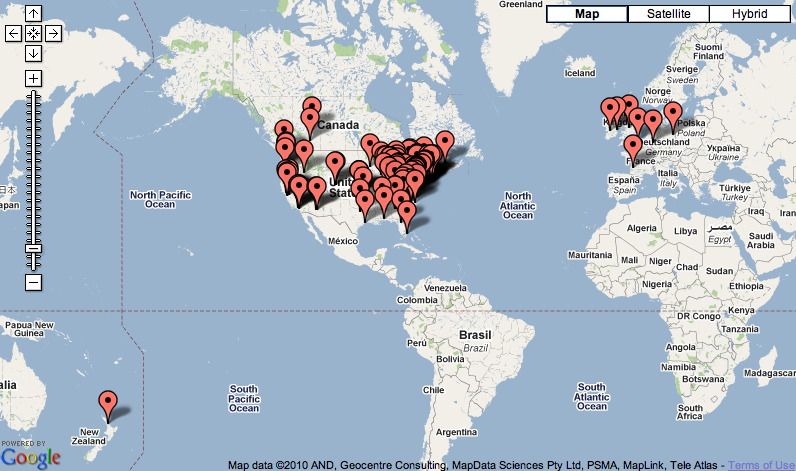

- Mirrored versions of Great Books – By searching and browsing the Internet 222 of the 260 Great Books were found and copied locally, giving us a constant (d) equal to 222.

- Indexed the corpus – An inverted index was created. I used Solr for this. [8]

- Calculated TFIDF for a given Great Idea – First the given Great Idea was stemmed and searched against the the index resulting in a value for f. Each Great Book was retrieved from the local mirror whereby the size of the work (t) was determined as well as the number of times the stem appeared in the work (c). TFIDF was then calculated.

- Repeated Step #3 for each of the Great Ideas – Go to Step #3 each of the Great Ideas.

- Summed each of the TFIDF scores – The Great Idea TFIDF scores were added together giving us our first Great Ideas Coefficient for a given work.

- Saved the result – Each of the individual scores as well as the Great Ideas Coefficient was saved to a database.

- Returned to Step #3 for each of the Great Books – Go to Step #3 each of the other works in the corpus.

The end result was a file in the form of a matrix with 222 rows and 104 columns. Each row represents a Great Book. Each column is a local identifier, a Great Ideas TFIDF score, and a book’s Great Ideas Coefficient. [9]

The Great Books analyzed

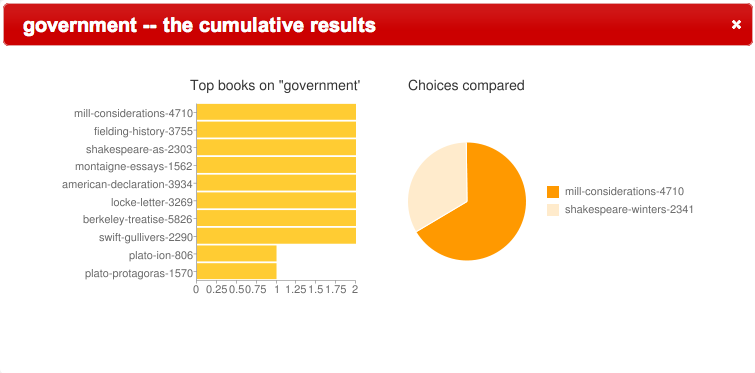

Sorting the matrix according to the Great Ideas Coefficient is trivial. Upon doing so I see that Kant’s Introduction To The Metaphysics Of Morals and Aristotle’s Politics are the first and second greatest books, respectively. When the matrix is sorted by the love column, I see Plato’s Symposium come out as number one, but Shakespeare claims seven of the top ten items with his collection of Sonnets being the first. When the matrix is sorted by the war column, then Aristophanes’s Peace is the greatest.

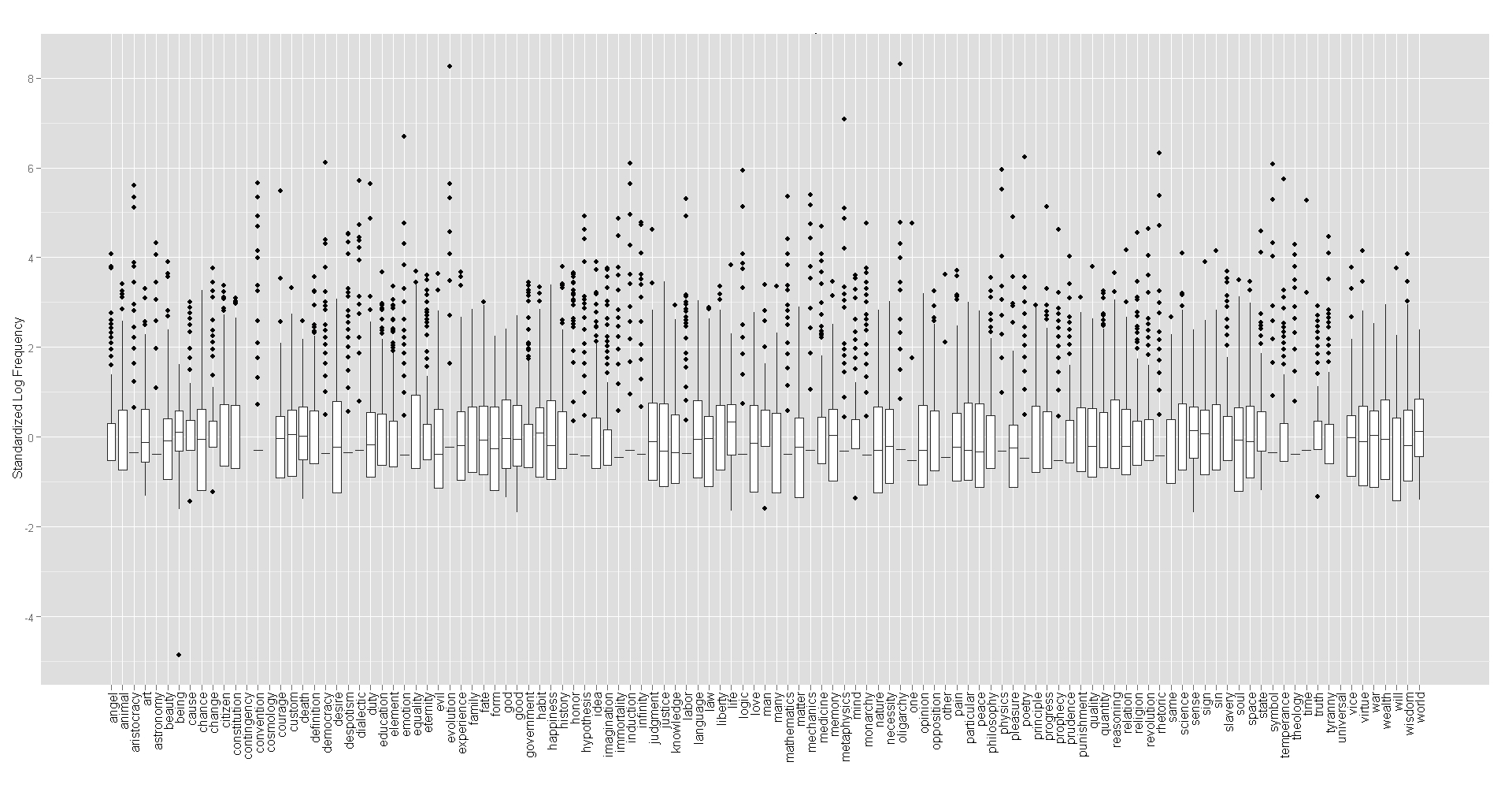

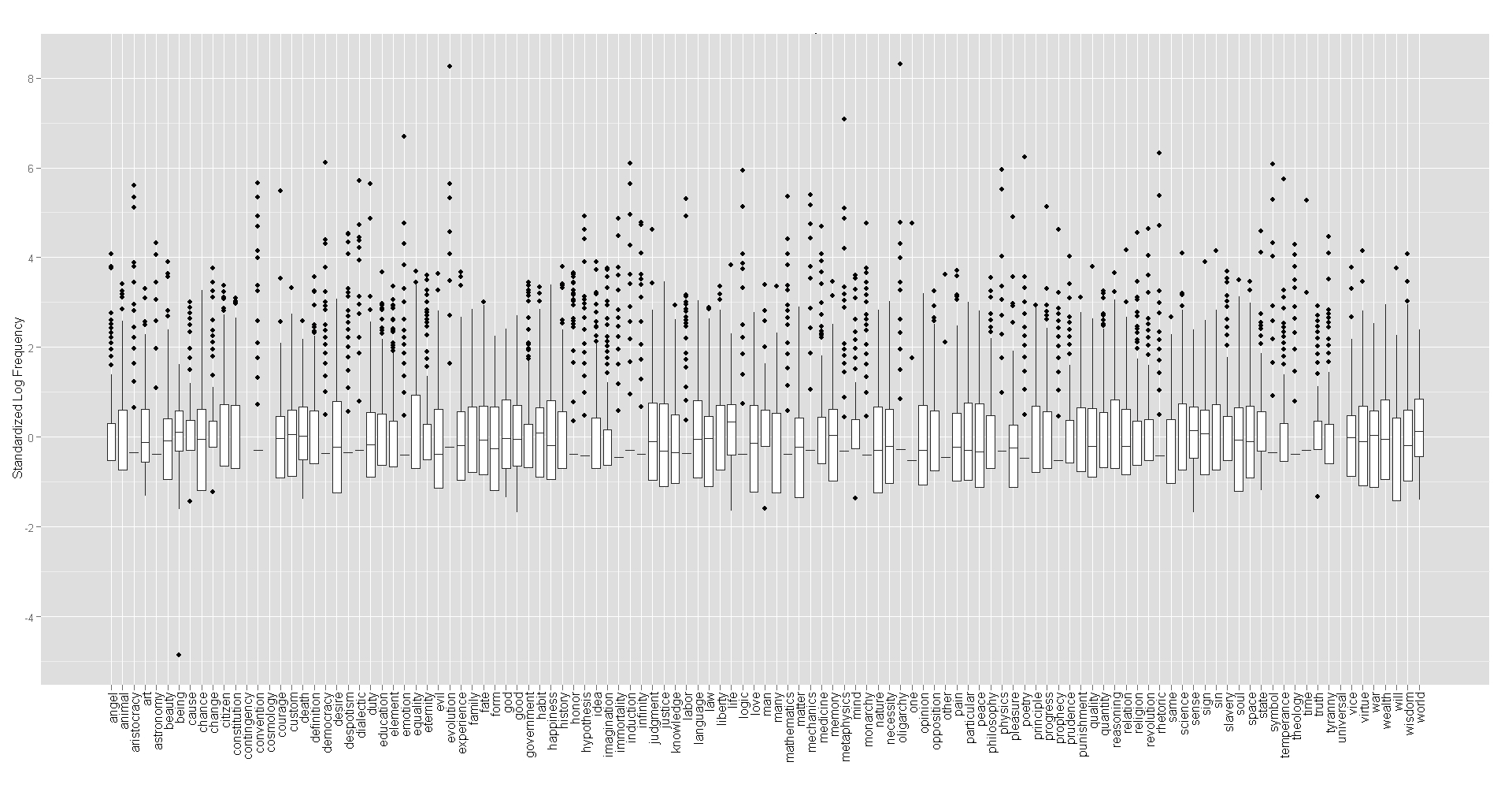

Unfortunately, denoting overall greatness in the previous manner is too simplistic because it does not fit the definition of greatness posited by Hutchins. The Great Books are expected to be great because they exemplify the “greatest range of imaginative or intellectual content”. In other words, the Great Books are great because they discuss and elaborate upon a wide spectrum of the Great Ideas, not just a few. Ironically, this does not seem to be the case. Most of the Great Books have many Great Idea scores equal to zero. In fact, at least two of the Great Ideas – cosmology and universal – have TFIDF scores equal to zero across the entire corpus, as illustrated by Figure 1. This being the case, I might say that none of the Great Books are truly great because none of them significantly discuss the totality of the Great Ideas.

Figure 1 – Box plot scores of Great Ideas

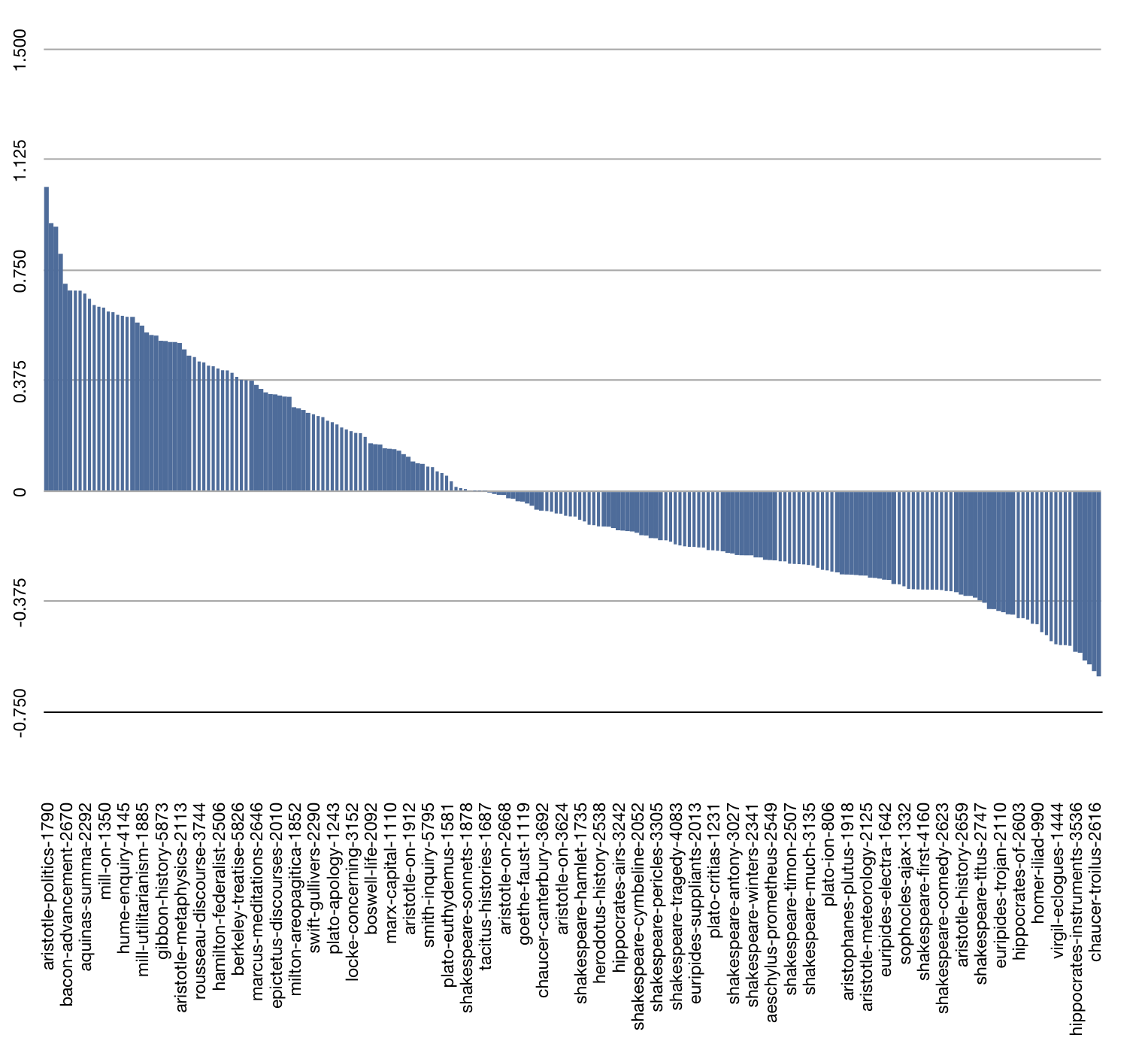

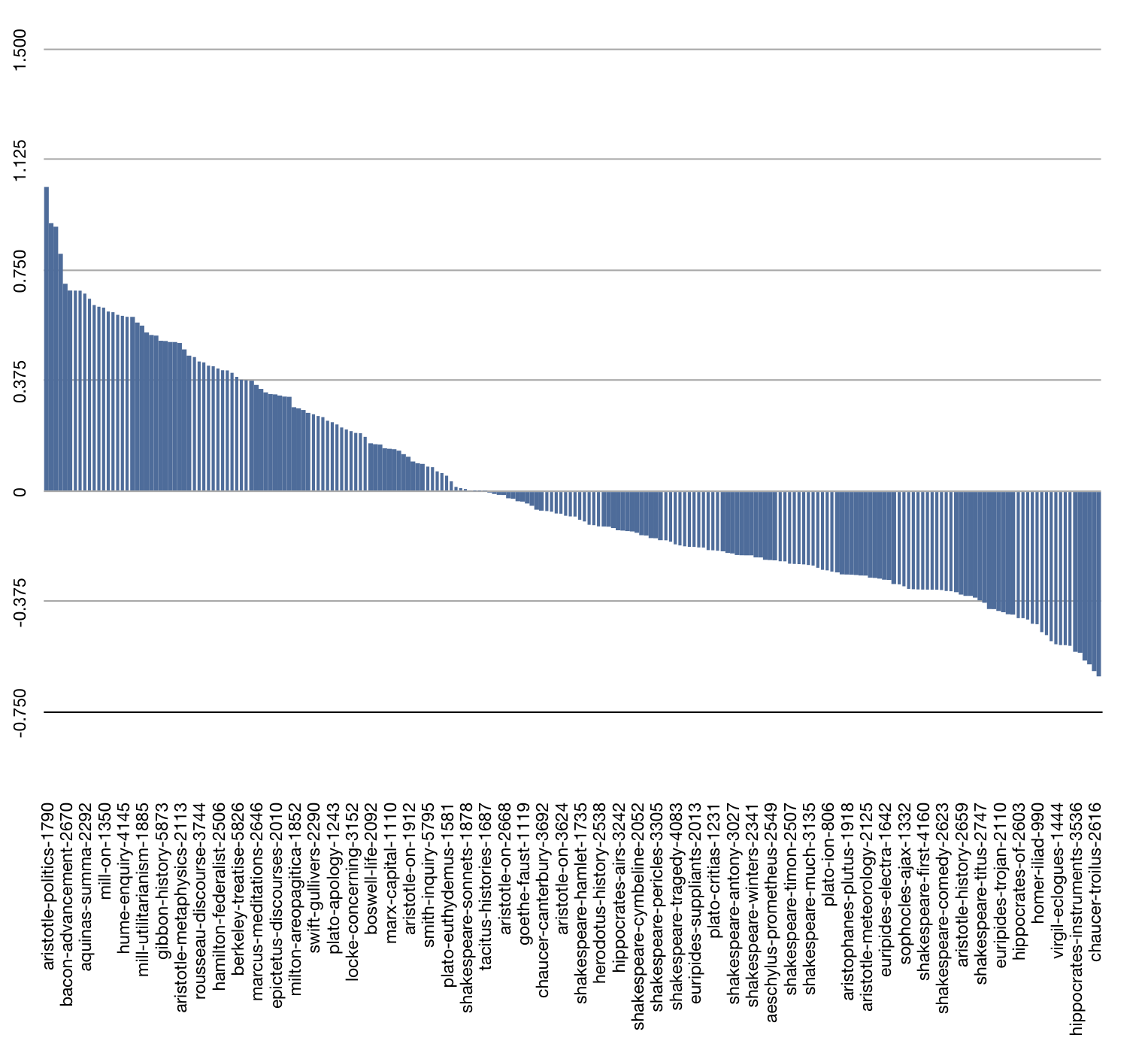

To take this into account and not allow the value of the Great Idea Coefficient to be overwhelmed by one or two Great Idea scores, I calculated the mean TFIDF score for each of the Great Ideas across the matrix. This vector represents an imaginary but “typical” Great Book. I then compared the Great Idea TFIDF scores for each of the Great Books with this central quantity to determine whether or not it is above or below the typical mean. After graphing the result I see that Aristotle’s Politics is still the greatest book with Hegel’s Philosophy Of History being number two, and Plato’s Republic being number three. Figure 2 graphically illustrates this finding, but in a compressed form. Not all works are listed in the figure.

Figure 2 – Individual books compared to the “typical” Great Book

Summary

How “great” are the Great Books? The answer depends on what qualities a person wants to measure. Aristotle’s Politics is great in many ways. Shakespeare is great when it comes to the idea of love. The calculation of the Great Ideas Coefficient is one way to compare & contrast texts in a corpus – “syntopical reading” in a digital age.

Notes

[1] Hutchins, Robert Maynard. 1952. Great books of the Western World. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica.

[2] Ibid. Volume 1, page xiv.

[3] Ibid. Volume 2, page xi.

[4] Moretti, Franco. 2005. Graphs, maps, trees: abstract models for a literary history. London: Verso, page 1.

[5] Hutchins, op. cit. Volume 3, page 1220.

[6] Manning, Christopher D., Prabhakar Raghavan, and Hinrich Schütze. 2008. An introduction to information retrieval. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, page 109.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Solr – http://lucene.apache.org/solr/

[9] This file – the matrix of identifiers and scores – is available at http://bit.ly/cLmabY, but a more useful and interactive version is located at http://bit.ly/cNVKnE