This posting outlines how I refined a number of my RSS feeds and then aggregated them into a coherent whole using Planet.

Many different RSS feeds

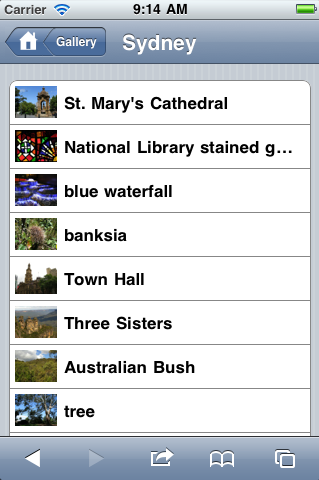

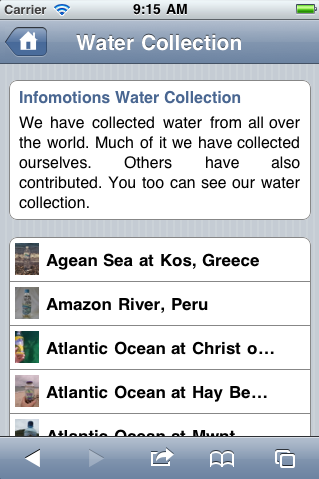

I have, more or less, been creating RSS (Real Simple Syndication) feeds since 2002. My first foray was not really with RSS but rather with RDF. At that time the functions of RSS and RDF were blurred. In any event, I used RDF as a way of syndicating randomly selected items from my water collection. I never really pushed the RDF, and nothing really became of it. See “Collecting water and putting it on the Web” for details.

In December of 2004 I started marking up my articles, presentations, and travelogues in TEI and saving the result in a database. The webified version of these efforts was something called Musings on Information and Librarianship. I described the database supporting the process is a specific entry called “My personal TEI publishing system“. A program — make-rss.pl — was used to make the feed.

Since then blogs have become popular, and almost by definition, blogs support RSS in a really big way. My RSS was functional, but by comparison, everybody else’s was exceptional. For many reasons I started drifting away from my personal publishing system in 2008 and started moving towards WordPress. This manifested itself in this blog — Mini-Musings.

To make things more complicated, I started blogging on other sites for specific purposes. About a year ago I started blogging for the “Catholic Portal”, and more recently I’ve been blogging about research data management/curation — Days in the Life of a Librarian — at the University of Notre Dame.

In September of 2009 I started implementing a reading list application. Print an article. Read it. Draw and scribble on it. (Read, “Annotate it.”) Scan it. Convert it into a PDF document. Do OCR against it. Save the result to a Web-accessible file system. Do data entry against a database to describe it. Index the metadata and extracted OCR. And finally, provide a searchable/browsable interface to the whole lot. The result is a fledgling system I call “What’s Eric Reading?” Since I wanted to share my wealth (after all, I am a librarian) I created an RSS feed against this system too.

I was on a roll. I went back to my water collection and created a full-fledged RSS feed against it as well. See the simple Perl script — water2rss.pl — to see how easy it is.

Ack! I now have six different active RSS feeds, not counting the feeds I can get from Flickr and YouTube:

That’s too many, even for an ego surfer like myself. What to do? How can I consolidate these things? How can I present my writings in a single interface? How can I make it easy to syndicate all of this content in a standards-compliant way?

Planet

The answer to my questions is/was Planet — “an awesome ‘river of news’ feed reader. It downloads news feeds published by web sites and aggregates their content together into a single combined feed, latest news first.”

A couple of years ago the Code4Lib community created an RSS “planet” called Planet Code4Lib — “Blogs and feeds of interest to the Code4Lib community, aggregated.” I think it is maintained by Jonathan Rochkind, but I’m not sure. It is pretty nice since it brings together the RSS feeds from quite a number of library “hackers”. Similarly, there is another planet called Planet Cataloging which does the same thing for library cataloging feeds. This one is maintained by Jennifer W. Baxmeyer and Kevin S. Clarke. The combined planets work very well together, except when individual blogs are in both aggregations. When this happens I end up reading the same blog postings twice. Not a big deal. You get what you pay for.

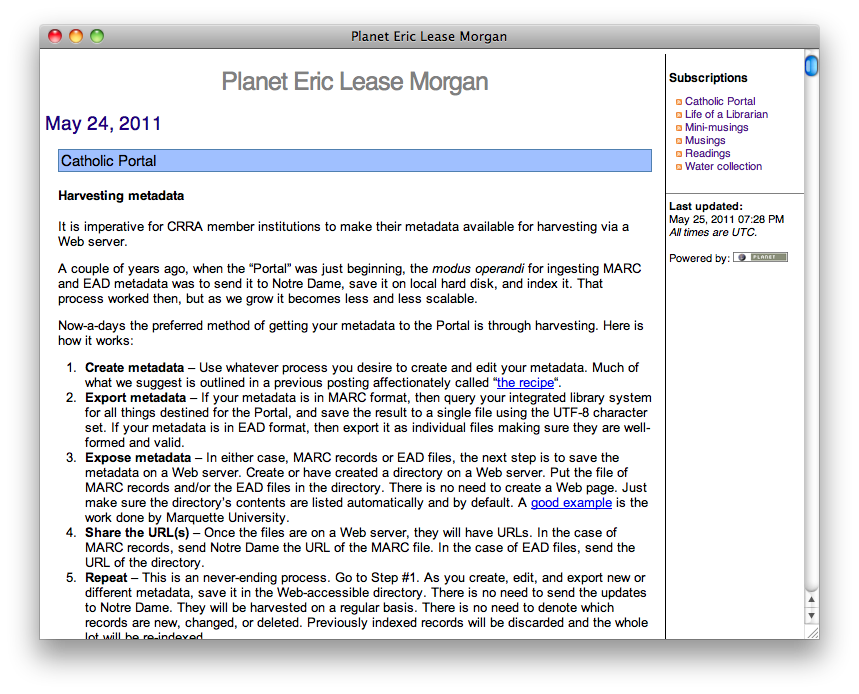

After a tiny bit of investigation, I decided to use Planet to aggregate and serve my RSS feeds. Installation and configuration was trivial. Download and unpack the distribution. Select an HTML template. Edit a configuration file denoting the location of RSS feeds and where the output will be saved. Run the program. Tweak the template. Repeat until satisfied. Run the program on a regular basis, preferably via cron. Done. My result is called Planet Eric Lease Morgan.

The graphic design may not be extraordinarily beautiful, but the content is not necessarily intended to be read via an HTML page. Instead the content is intended to be read from inside one’s favorite RSS reader. Planet not only aggregates content but syndicates it too. Very, very nice.

What I learned

I learned a number of things from this process. First I learned that standards evolve. “Duh!”

Second, my understanding of open source software and its benefits was re-enforced. I would not have been able to do nearly as much if it weren’t for open source software.

Third, the process provided me with a means to reflect on the processes of librarianship. My particular processes for syndicating content needed to evolve in order to remain relevant. I had to go back and modify a number of my programs in order for everything to work correctly and validate. The library profession seemingly hates to do this. We have a mindset of “Mark it and park it.” We have a mindset of “I only want to touch book or record once.” In the current environment, this is not healthy. Change is more the norm than not. The profession needs to embrace change, but then again, all institutions, almost by definition, abhor change. What’s a person to do?

Forth, the process enabled me to come up with a new quip. The written word read transcends both space and time. Fun!?

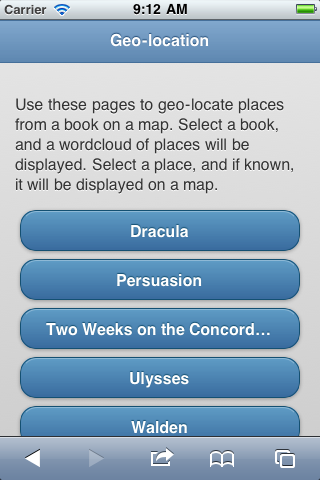

Finally, here’s an idea for the progressive librarians in the crowd. Use the Planet software to aggregate RSS fitting your library’s collection development policy. Programatically loop through the resulting links to copy/mirror the remote content locally. Curate the resulting collection. Index it. Integrate the subcollection and index into your wider collection of books, jourals, etc. Repeat.