With the advent of the Internet and wide-scale availability of full-text content, people are overwhelmed with the amount of accessible data and information. Library catalogs can only go so far when it comes to delimiting what is relevant and what is not. Even when the most exact searches return 100’s of hits what is a person to do? Services against texts — digital humanities computing techniques — represent a possible answer. Whether the content is represented by novels, works of literature, or scholarly journal articles the methods of the digital humanities can provide ways to compare & contrast, analyze, and make more useful any type of content. This essay elaborates on these ideas and describes how they can be integrated into the “next, next-generation library catalog”.

(Because this essay is the foundation for a presentation at the 2010 ALA Annual Meeting, this presentation is also available as a one-page handout designed for printing as well as bloated set of slides.)

Find is not the problem

Find is not the problem to be solved. At most, find is a means to an end and not the end itself. Instead, the problem to solve surrounds use. The profession needs to implement automated ways to make it easier users do things against content.

The library profession spends an inordinate amount of time and effort creating catalogs — essentially inventory lists of things a library owns (or licenses). The profession then puts a layer on top of this inventory list — complete with authority lists, controlled vocabularies, and ever-cryptic administrative data — to facilitate discovery. When poorly implemented, this discovery layer is seen by the library user as an impediment to their real goal. Read a book or article. Verify a fact. Learn a procedure. Compare & contrast one idea with another idea. Etc.

In just the past few years the library profession has learned that indexers (as opposed to databases) are the tools to facilitate find. This is true for two reasons. First, indexers reduce the need for users to know how the underlying data is structured. Second, indexers employ statistical analysis to rank it’s output by relevance. Databases are great for creating and maintaining content. Indexers are great for search. Both are needed in equal measures in order to implement the sort of information retrieval systems people have come to expect. For example, many of the profession’s current crop of “discovery” systems (VUFind, Blacklight, Summon, Primo, etc.) all use an open source indexer called Lucene to drive search.

This being the case, we can more or less call the problem of find solved. True, software is never done, and things can always be improved, but improvements in the realm of search will only be incremental.

Instead of focusing on find, the profession needs to focus on the next steps in the process. After a person does a search and gets back a list of results, what do they want to do? First, they will want to peruse the items in the list. After identifying items of interest, they will want to acquire them. Once the selected items are in hand users may want to print, but at the very least they will want to read. During the course of this reading the user may be doing any number of things. Ranking. Reviewing. Annotating. Summarizing. Evaluating. Looking for a specific fact. Extracting the essence of the author’s message. Comparing & contrasting the text to other texts. Looking for sets of themes. Tracing ideas both inside and outside the texts. In other words, find and acquire are just a means to greater ends. Find and acquire are library goals, not the goals of users.

People want to perform actions against the content they acquire. They want to use the content. They want to do stuff with it. By expanding our definition of “information literacy” to include things beyond metadata and bibliography, and by combining it with the power of computers, librarianship can further “save the time of the reader” and thus remain relevant in the current information environment. Focusing on the use and evaluation of information represents a growth opportunity for librarianship.

It starts with counting

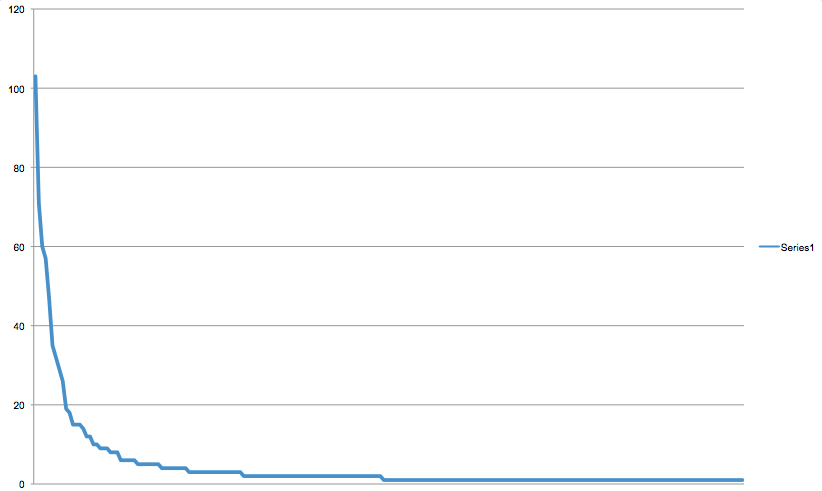

The availability of full text content in the form of plain text files combined with the power of computing empowers one to do statistical analysis against corpora. Put another way, computers are great at counting words, and once sets of words are counted there are many things one can do with the results, such as but not limited to:

- measuring length

- measuring readability, “greatness”, or any other index

- measuring frequency of unigrams, n-grams, parts-of-speech, etc.

- charting & graphing analysis (word clouds, scatter plots, histograms, etc.)

- analyzing measurements and looking for patterns

- drawing conclusions and making hypotheses

For example, suppose you did the perfect search and identified all of the works of Plato, Aristotle, and Shakespeare. Then, if you had the full text, you could compute a simple table such as Table 1.

| Author |

Works |

Words |

Average |

Grade |

Flesch |

| Plato |

25 |

1,162,46 |

46,499 |

12-15 |

54 |

| Aristotle |

19 |

950,078 |

50,004 |

13-17 |

50 |

| Shakespeare |

36 |

856,594 |

23,794 |

7-10 |

72 |

The table lists who wrote how many works. It lists the number of words in each set of works and the average number of words per work. Finally, based on things like sentence length, it estimates grade and reading levels for the works. Given such information, a library “catalog” could help the patron could answer questions such as:

- Which author has the most works?

- Which author has the shortest works?

- Which author is the most verbose?

- Is the author of most works also the author who is the most verbose?

- In general, which set of works requires the higher grade level?

- Does the estimated grade/reading level of each authors’ work coincide with one’s expectations?

- Are there any authors whose works are more or less similar in reading level?

Given the full text, a trivial program can then be written to count the number of words existing in a corpus as well as the number of times each word occurs, as shown in Table 2.

| Plato |

Aristotle |

Shakespeare |

| will |

one |

thou |

| one |

will |

will |

| socrates |

must |

thy |

| may |

also |

shall |

| good |

things |

lord |

| said |

man |

thee |

| man |

may |

sir |

| say |

animals |

king |

| true |

thing |

good |

| shall |

two |

now |

| like |

time |

come |

| can |

can |

well |

| must |

another |

enter |

| another |

part |

love |

| men |

first |

let |

| now |

either |

hath |

| also |

like |

man |

| things |

good |

like |

| first |

case |

one |

| let |

nature |

upon |

| nature |

motion |

know |

| many |

since |

say |

| state |

others |

make |

| knowledge |

now |

may |

| two |

way |

yet |

Table 2, sans a set of stop words, lists the most frequently used words in the complete works of Plato, Aristotle, and Shakespeare. The patron can then ask and answer questions like:

- Are there words in one column that appear frequently in all columns?

- Are there words that appear in only one column?

- Are the rankings of the words similar between columns?

- To what degree are the words in each column a part of larger groups such as: nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.?

- Are there many synonyms or antonyms shared inside or between the columns?

Notice how the words “one”, “good” and “man” appear in all three columns. Does that represent some sort of shared quality between the works?

If one word contains some meaning, then do two words contain twice as much meaning? Here is a list of the most common two-word phrases (bigrams) in each author corpus, Table 3.

| Plato |

Aristotle |

Shakespeare |

| let us |

one another |

king henry |

| one another |

something else |

thou art |

| young socrates |

let uses |

thou hast |

| just now |

takes place |

king richard |

| first place |

one thing |

mark antony |

| every one |

without qualification |

prince henry |

| like manner |

middle term |

let us |

| every man |

first figure |

king lear |

| quite true |

b belongs |

thou shalt |

| two kinds |

take place |

duke vincentio |

| human life |

essential nature |

dost thou |

| one thing |

every one |

sir toby |

| will make |

practical wisdom |

art thou |

| human nature |

will belong |

henry v |

| human mind |

general rule |

richard iii |

| quite right |

anything else |

toby belch |

| modern times |

one might |

scene ii |

| young men |

first principle |

act iv |

| can hardly |

good man |

iv scene |

| will never |

two things |

exeunt king |

| will tell |

two kinds |

don pedro |

| dare say |

first place |

mistress quickly |

| will say |

like manner |

act iii |

| false opinion |

one kind |

thou dost |

| one else |

scientific knowledge |

sir john |

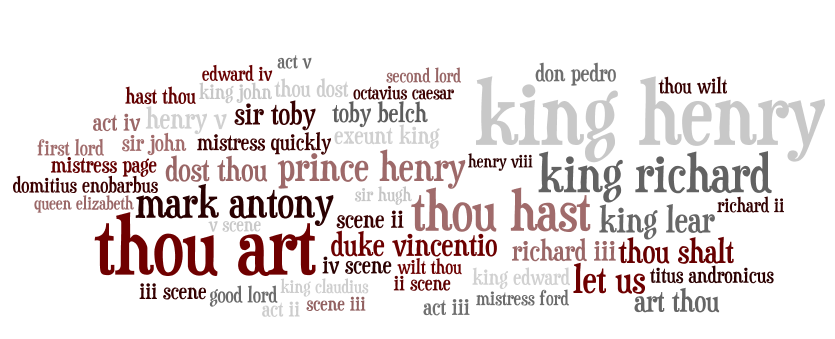

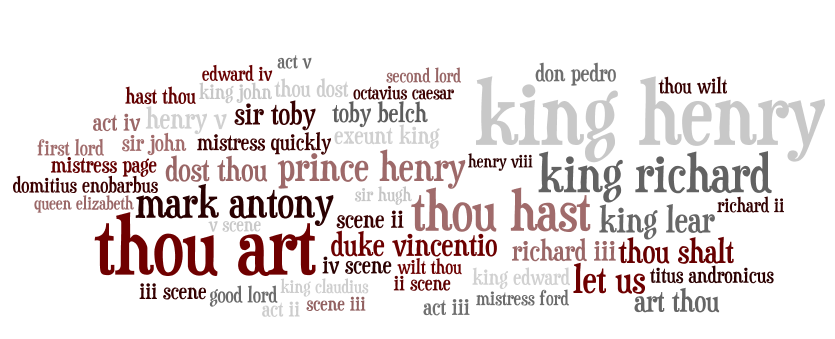

Notice how the names of people appear frequently in Shakespeare’s works, but very few names appear in the lists of Plato and Aristotle. Notice how the word “thou” appears a lot in Shakespeare’s works. Ask yourself the meaning of the word “thou”, and decide whether or not to update the stop word list. Notice how the common phrases of Plato and Aristotle are akin to ideas, not tangible things. Examples include: human nature, practical wisdom, first principle, false opinion, etc. Is there a pattern here?

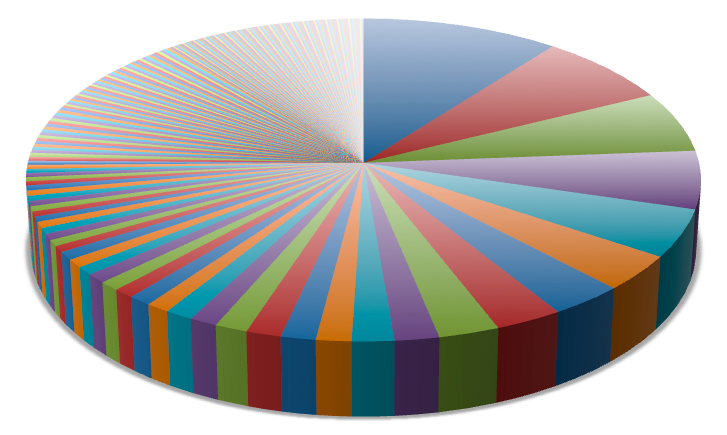

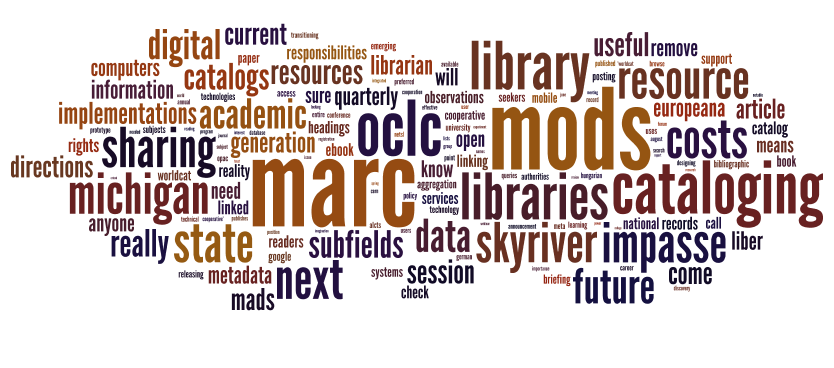

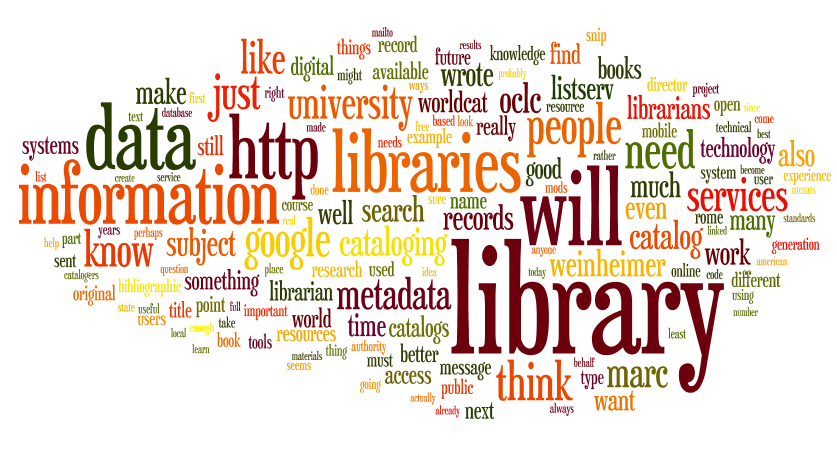

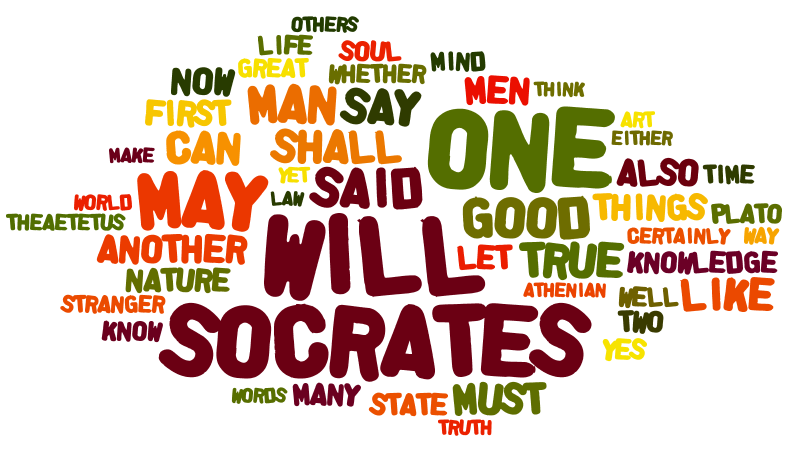

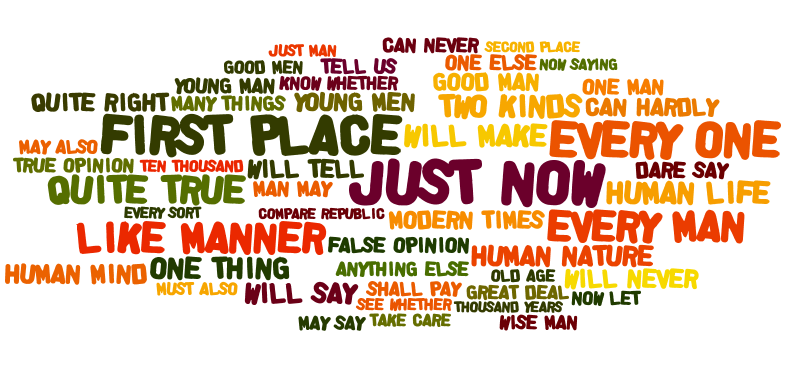

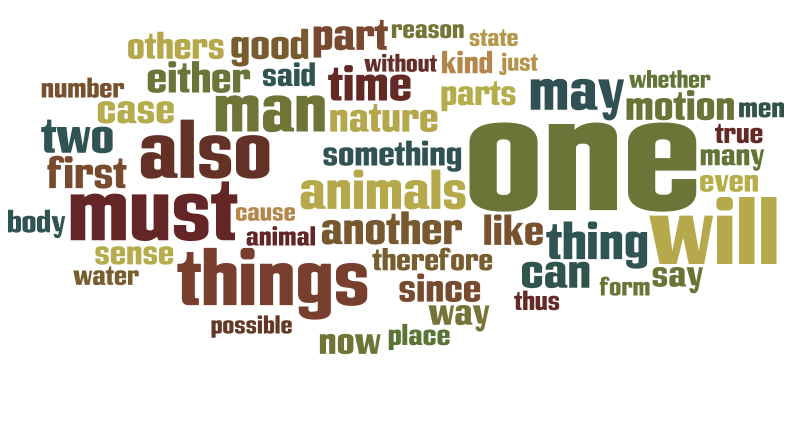

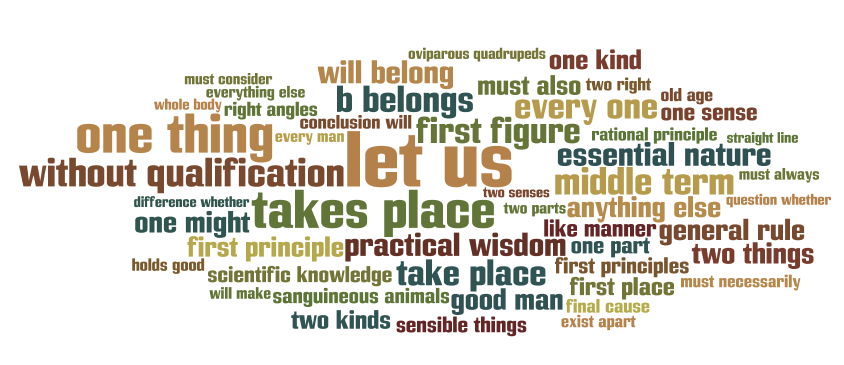

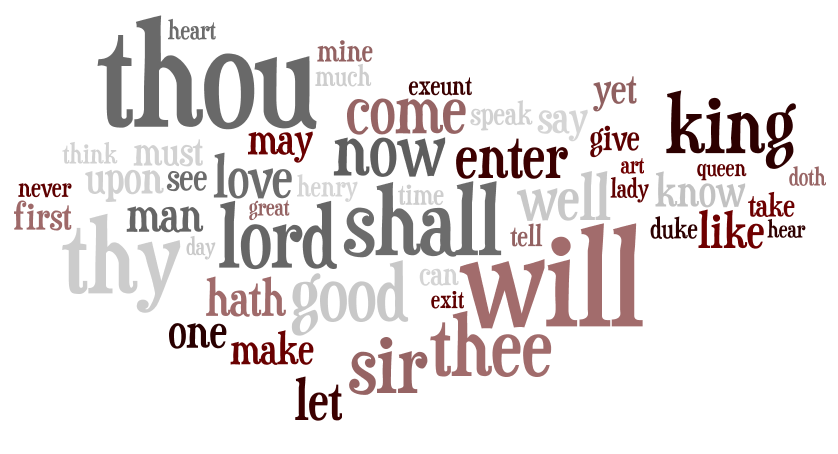

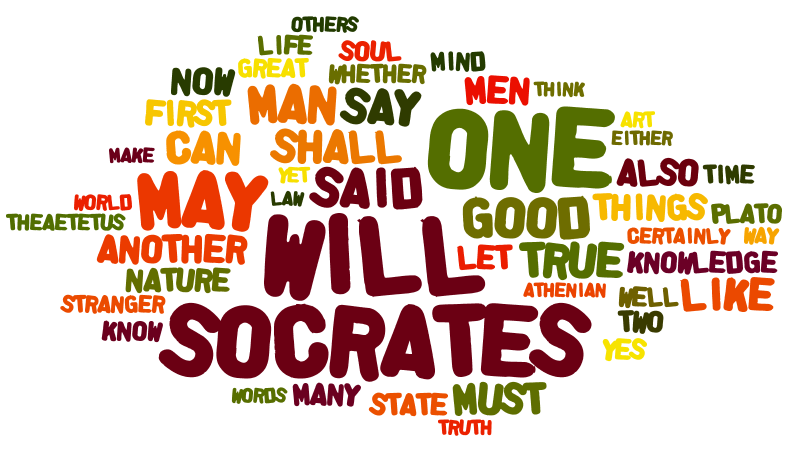

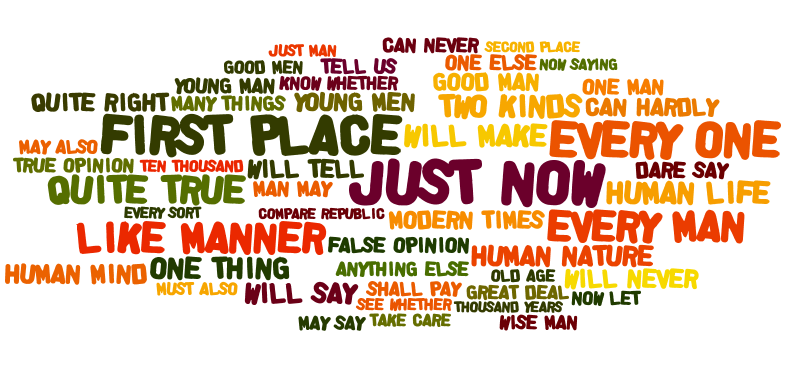

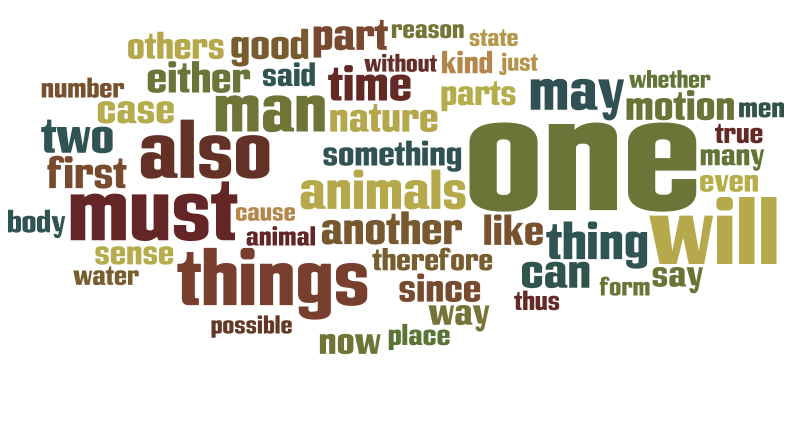

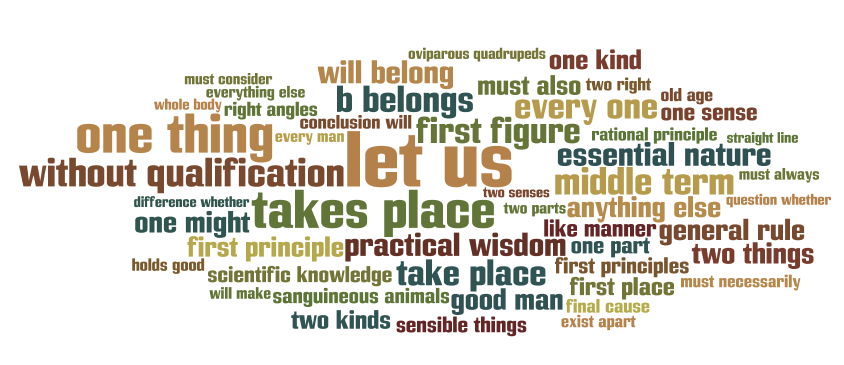

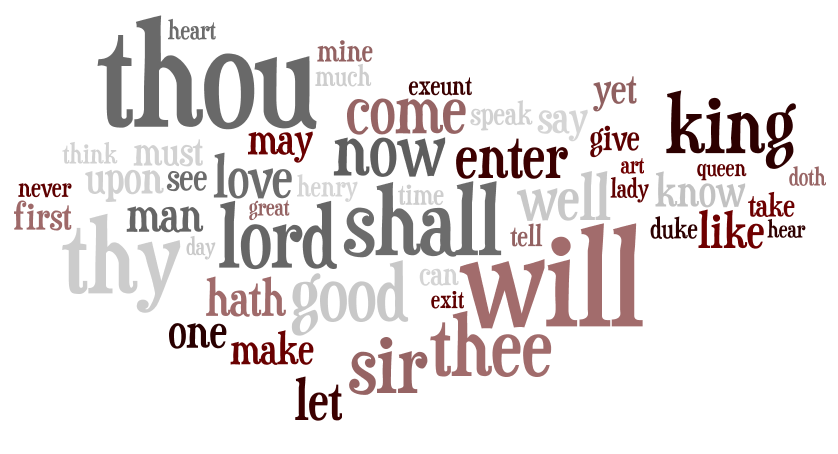

If “a picture is worth a thousand words”, then there are about six thousand words represented by Figures 1 through 6.

Words used by Plato

|

Phrases used by Plato

|

Words used by Aristotle

|

Phrases used by Aristotle

|

Words used by Shakespeare

|

Phrases used by Shakespeare

|

Word clouds — “tag clouds” — are an increasingly popular way to illustrate the frequency of words or phrases in a corpus. Because a few of the phrases in a couple of the corpuses were considered outliers, phrases such as “let us”, “one another”, and “something else” are not depicted.

Even without the use of statistics, it appears the use of the phrase “good man” by each author might be interestingly compared & contrasted. A concordance is an excellent tool for such a purpose, and below are a few of the more meaty uses of “good man” by each author.

| List 1 – “good man” as used by Plato |

ngth or mere cleverness. To the good man, education is of all things the most pr

Nothing evil can happen to the good man either in life or death, and his own de

but one reply: 'The rule of one good man is better than the rule of all the rest

SOCRATES: A just and pious and good man is the friend of the gods; is he not? P

ry wise man who happens to be a good man is more than human (daimonion) both in

|

| List 2 – “good man” as used by Aristotle |

ons that shame is felt, and the good man will never voluntarily do bad actions.

reatest of goods. Therefore the good man should be a lover of self (for he will

hat is best for itself, and the good man obeys his reason. It is true of the goo

theme If, as I said before, the good man has a right to rule because he is bette

d prove that in some states the good man and the good citizen are the same, and

|

| List 3 – “good man” as used by Shakespeare |

r to that. SHYLOCK Antonio is a good man. BASSANIO Have you heard any imputation

p out, the rest I'll whistle. A good man's fortune may grow out at heels: Give y

t it, Thou canst not hit it, my good man. BOYET An I cannot, cannot, cannot, An

hy, look where he comes; and my good man too: he's as far from jealousy as I am

mean, that married her, alack, good man! And therefore banish'd -- is a creatur

|

What sorts of judgements might the patron be able to make based on the snippets listed above? Are Plato, Aristotle, and Shakespeare all defining the meaning of a “good man”? If so, then what are some of the definitions? Are there qualitative similarities and/or differences between the definitions?

Sometimes being as blunt as asking a direct question, like “What is a man?”, can be useful. Lists 4 through 6 try to answer it.

| List 4 – “man is” as used by Plato |

stice, he is met by the fact that man is a social being, and he tries to harmoni

ption of Not-being to difference. Man is a rational animal, and is not -- as man

ss them. Or, as others have said: Man is man because he has the gift of speech;

wise man who happens to be a good man is more than human (daimonion) both in lif

ied with the Protagorean saying, 'Man is the measure of all things;' and of this

|

| List 5 – “man is” as used by Aristotle |

ronounced by the judgement 'every man is unjust', the same must needs hold good

ts are formed from a residue that man is the most naked in body of all animals a

ated piece at draughts. Now, that man is more of a political animal than bees or

hese vices later. The magnificent man is like an artist; for he can see what is

lement in the essential nature of man is knowledge; the apprehension of animal a

|

| List 6 – “man is” as used by Shakespeare |

what I have said against it; for man is a giddy thing, and this is my conclusio

of man to say what dream it was: man is but an ass, if he go about to expound t

e a raven for a dove? The will of man is by his reason sway'd; And reason says y

n you: let me ask you a question. Man is enemy to virginity; how may we barricad

er, let us dine and never fret: A man is master of his liberty: Time is their ma

|

In the 1950s Mortimer Adler and a set of colleagues created a set of works they called The Great Books of the Western World. This 80-volume set included all the works of Plato, Aristotle, and Shakespeare as well as some of the works of Augustine, Aquinas, Milton, Kepler, Galileo, Newton, Melville, Kant, James, and Frued. Prior to the set’s creation, Adler and colleagues enumerated 102 “greatest ideas” including concepts such as: angel, art, beauty, honor, justice, science, truth, wisdom, war, etc. Each book in the series was selected for inclusion by the committee because of the way the books elaborated on the meaning of the “great ideas”.

Given the full text of each of the Great Books as well as a set of keywords (the “great ideas”), it is relatively simple to calculate a relevancy ranking score for each item in a corpus. Love is one of the “great ideas”, and it just so happens it is used most significantly by Shakespeare compared to the use of the other authors in the set. If Shakespeare has the highest “love quotient”, then what does Shakespeare have to say about love? List 7 is a brute force answer to such a question.

| List 7 – “love is” as used by Shakespeare |

y attempted? Love is a familiar; Love is a devil: there is no evil angel but Lov

er. VALENTINE Why? SPEED Because Love is blind. O, that you had mine eyes; or yo

that. DUKE This very night; for Love is like a child, That longs for every thin

n can express how much. ROSALIND Love is merely a madness, and, I tell you, dese

of true minds Admit impediments. Love is not love Which alters when it alteratio

|

Do these definitions coincide with expectations? Maybe further reading is necessary.

Digital humanities, library science, and “catalogs”

The previous section is just about the most gentle introduction to digital humanities computing possible, but can also be an introduction to a new breed of library science and library catalogs.

It began by assuming the existence of full text content in plain text form — an increasingly reasonable assumption. After denoting a subset of content, it compared & contrasted the sizes and reading levels of the content. By counting individual words and phrases, patterns were discovered in the texts and a particular idea was loosely followed — specifically, the definition of a good man. Finally, the works of a particular author were compared to the works of a larger whole to learn how the author defined a particular “great idea”.

The fundamental tools used in this analysis were a set of rudimentary Perl modules: Lingua::EN::Fathom for calculating the total number of words in a document as well as a document’s reading level, Lingua::EN::Bigram for listing the most frequently occurring words and phrases, and Lingua::Concordance for listing sentence snippets. The Perl programs built on top of these modules are relatively short and include: fathom.pl, words.pl, bigrams.pl and concordance.pl. (If you really wanted to download the full text versions of Plato, Aristotle, and Shakespeare‘s works used in this analysis.) While the programs themselves are really toys, the potential they represent are not. It would not be too difficult to integrate their functionality into a library “catalog”. Assume the existence of significant amount of full text content in a library collection. Do a search against the collection. Create a subset of content. Click a few buttons to implement statistical analysis against the result. Enable the user to “browse” the content and follow a line of thought.

The process outlined in the previous section is not intended to replace rigorous reading, but rather to supplement it. It enables a person to identify trends quickly and easily. It enables a person to read at “Web scale”. Again, find is not the problem to be solved. People can find more information than they require. Instead, people need to use and analyze the content they find. This content can be anything from novels to textbooks, scholarly journal articles to blog postings, data sets to collections of images, etc. The process outlined above is an example of services against texts, a way to “Save the time of the reader” and empower them to make better and more informed decisions. The fundamental processes of librarianship (collection, preservation, organization, and dissemination) need to be expanded to fit the current digital environment. The services described above are examples of how processes can be expanded.

The next “next generation library catalog” is not about find, instead it is about use. Integrating digital humanities computing techniques into library collections and services is just one example of how this can be done.

This is the briefest of travelogues describing my experience at the 2010 ALA Annual Meeting in Washington (DC).

This is the briefest of travelogues describing my experience at the 2010 ALA Annual Meeting in Washington (DC).