On Thursday, September 4 a person from Google named Jon Trowbridge gave a presentation at Notre Dame called “Making scientific datasets universally accessible and useful”. This posting reports on the presentation and dinner afterwards.

The presentation

Jon Trowbridge is a software engineer working for Google. He seems to be an open source software and an e-science type of guy who understands academia. He echoed the mission of Google — “To organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful”, and he described how this mission fits into his day-to-day work. (I sort of wish libraries would have such a easily stated mission. It might clear things up and give us better focus.)

Trowbridge works for group in Google exploring ways to making large datasets available. He proposes to organize and distribute datasets in the same manner open source software is organized.

He enumerated things people do with data of this type: compute against it, visualize it, search it, do meta-analysis, and create mash-ups. But all of this begs Question 0. “You have to possess the data before you can do stuff with it.” (This is also true in libraries, and this is why I advocate digitization as oppose to licensing content.)

He speculated why scientists have trouble distributing their data, especially if it more than a terabyte in size. URLs break. Datasets are not very indexable. Datasets of the fodder for new research. He advocated the creation of centralized data “clouds”, and these “clouds” ought to have the following qualities:

- archival

- librarian-friendly (have some metadata)

- citation-friendly

- publicly accessible

- legally unencumbered

- discipline neutral

- massively scalable

- downloadable via HTTP

As he examined people’s datasets he noticed that many of them are simple hierarchal structures saved to file systems, but they are so huge that transporting them over the network isn’t feasible. After displaying a few charts and graphs, he posited that physically shipping hard disks via FedEx provides the fastest throughput. Given that hard drives can cost as little as 16¢/GB, FedEx can deliver data at a rate of 20 TB/day. Faster and cheaper than the just about anybody’s network connection.

The challenge

Given this scenario, Trowbridge gave away 5 TB of hard disk disk space. He challenged us to fill it up with data and share it with him. He would load the data into his “cloud” and allow people to use it. This is just the beginning of an idea, not a formal service. Host data locally. Provide tools to access and use it. Support e-science.

Personally, I thought it was a pretty good idea. Yes, Google is a company. Yes, I wonder to what degree I can trust Google. Yes, if I make my data accessible then I don’t have a monopoly on it, and others will may beat me to the punch. On the other hand, Google has so much money that they can afford to “Do no evil.” I sincerely doubt anybody was trying to pull the wool over our eyes.

Dinner with Jon

After the presentation I and a couple of my colleagues (Mark Dehmlow and Dan Marmion) had dinner with Jon. We discussed what it is like to work for Google. The hiring process. The similarities and differences between Google and libraries. The weather. Travel. Etc.

All in all, I thought it was a great experience. “Thank you for the opportunity!” It is always nice to chat with sets of my peers about my vocation (as well as my avocation).

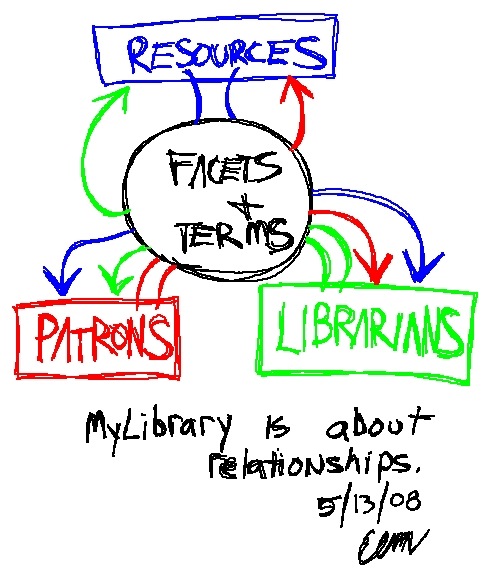

Unfortunately, we never really got around to talking about the use of data, just its acquisition. The use of data is a niche I believe libraries can fill and Google can’t. Libraries are expected to know their audience. Given this, information acquired through a library settings can be put into the user’s context. This context-setting is a service. Beyond that, other services can be provided against the data. Translate. Analyze. Manipulate. Create word cloud. Trace idea forward and backward. Map. Cite. Save for later and then search. Etc. These are spaces where libraries can play a role, and the lynchpin is the acquisition of the data/information. Other institutions have all but solved the search problem. It is now time to figure out how to put the information to use so we can stop drinking from the proverbial fire hose.

P.S. I don’t think very many people from Notre Dame will be taking Jon up on his offer to host their data.