This posting describes how a Perl module named Lingua::Concordance allows the developer to illustrate where in the continum of a text words or phrases appear and how often.

Windmills, my man Friday, and love

When it comes to Western literature and windmills, we often think of Don Quiote. When it comes to “my man Friday” we think of Robinson Crusoe. And when it comes to love we may very well think of Romeo and Juliet. But I ask myself, “How often do these words and phrases appear in the texts, and where?” Using digital humanities computing techniques I can literally illustrate the answers to these questions.

Lingua::Concordance

Lingua::Concordance is a Perl module (available locally and via CPAN) implementing a simple key word in context (KWIC) index. Given a text and a query as input, a concordance will return a list of all the snippets containing the query along with a few words on either side. Such a tool enables a person to see how their query is used in a literary work.

Given the fact that a literary work can be measured in words, and given then fact that the number of times a particular word or phrase can be counted in a text, it is possible to illustrate the locations of the words and phrases using a bar chart. One axis represents a percentage of the text, and the other axis represents the number of times the words or phrases occur in that percentage. Such graphing techniques are increasingly called visualization — a new spin on the old adage “A picture is worth a thousand words.”

In a script named concordance.pl I answered such questions. Specifically, I used it to figure out where in Don Quiote windmills are mentiond. As you can see below they are mentioned only 14 times in the entire novel, and the vast majority of the time they exist in the first 10% of the book.

$ ./concordance.pl ./don.txt 'windmill'

Snippets from ./don.txt containing windmill:

* DREAMT-OF ADVENTURE OF THE WINDMILLS, WITH OTHER OCCURRENCES WORTHY TO

* d over by the sails of the windmill, Sancho tossed in the blanket, the

* thing is ignoble; the very windmills are the ugliest and shabbiest of

* liest and shabbiest of the windmill kind. To anyone who knew the count

* ers say it was that of the windmills; but what I have ascertained on t

* DREAMT-OF ADVENTURE OF THE WINDMILLS, WITH OTHER OCCURRENCES WORTHY TO

* e in sight of thirty forty windmills that there are on plain, and as s

* e there are not giants but windmills, and what seem to be their arms a

* t most certainly they were windmills and not giants he was going to at

* about, for they were only windmills? and no one could have made any m

* his will be worse than the windmills," said Sancho. "Look, senor; thos

* ar by the adventure of the windmills that your worship took to be Bria

* was seen when he said the windmills were giants, and the monks' mules

* with which the one of the windmills, and the awful one of the fulling

A graph illustrating in what percentage of ./don.txt windmill is located:

10 (11) #############################

20 ( 0)

30 ( 0)

40 ( 0)

50 ( 0)

60 ( 2) #####

70 ( 1) ##

80 ( 0)

90 ( 0)

100 ( 0)

If windmills are mentioned so few times, then why do they play so prominently in people’s minds when they think of Don Quiote? To what degree have people read Don Quiote in its entirity? Are windmills as persistent a theme throughout the book as many people may think?

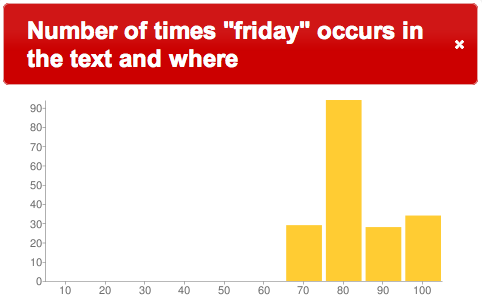

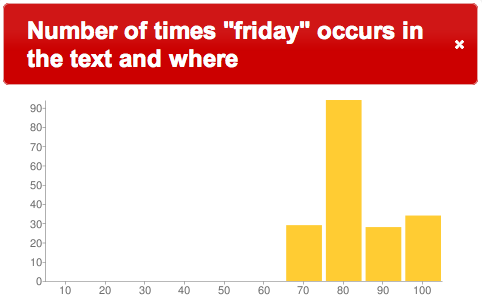

What about “my man Friday”? Where does he occur in Robinson Crusoe? Using the concordance features of the Alex Catalogue of Electronic Texts we can see that a search for the word Friday returns 185 snippets. Mapping those snippets to percentages of the text results in the following bar chart:

Friday in Robinson Crusoe

Obviously the word Friday appears towards the end of the novel, and as anybody who has read the novel knows, it is a long time until Robinson Crusoe actually gets stranded on the island and meets “my man Friday”. A concordance helps people understand this fact.

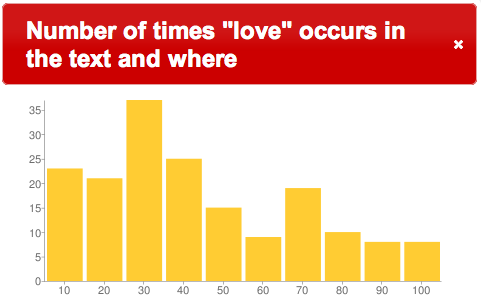

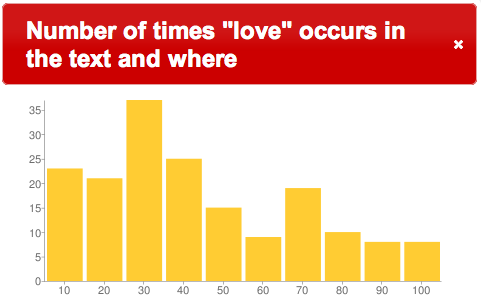

What about love in Romeo and Juliet? How often does the word occur and where? Again, a search for the word love returns quite a number of snippets (175 to be exact), and they are distributed throughout the text as illustrated below:

love in Romeo and Juliet

“Maybe love is a constant theme of this particular play,” I state sarcastically, and “Is there less love later in the play?”

Digital humanities and librarianship

Given the current environment, where full text literature abounds, digital humanities and librarianship are a match made in heaven. Our library “discovery systems” are essencially indexes. They enable people to find data and information in our collections. Yet find is not an end in itself. In fact, it is only an activity at the very beginning of the learning process. Once content is found it is then read in an attempt at understanding. Counting words and phrases, placing them in the context of an entire work or corpus, and illustrating the result is one way this understanding can be accomplished more quickly. Remember, “Save the time of the reader.”

Integrating digital humanities computing techniques, like concordances, into library “discovery systems” represent a growth opportunity for the library profession. If we don’t do this on our own, then somebody else will, and we will end up paying money for the service. Climb the learning curve now, or pay exorbitant fees later. The choice is ours.