The venerable Python Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) is well worth the time of anybody who wants to do text mining more programmatically. [0]

For much of my career, Perl has been the language of choice when it came to processing text, but in the recent past it seems to have fallen out of favor. I really don’t know why. Maybe it is because so many other computer languages have some into existence in the past couple of decades: Java, PHP, Python, R, Ruby, Javascript, etc. Perl is more than capable of doing the necessary work. Perl is well-supported, and there are a myriad of supporting tools/libraries for interfacing with databases, indexers, TCP networks, data structures, etc. On the other hand, few people are being introduced to Perl; people are being introduced to Python and R instead. Consequently, the Perl community is shrinking, and the communities for other languages is growing. Writing something in a “dead” language is not very intelligent, but that may be over-stating the case. On the other hand, I’m not going to be able to communicate with very many people if I speak Latin and everybody else is speaking French, Spanish, or German. It behooves the reader to write software in a language apropos to the task as well as a langage used by many others.

Python is a good choice for text mining and natural language processing. The Python NLTK provides functionality akin to much of what has been outlined in this workshop, but it goes much further. More specifically, it interaces with WordNet, a sort of thesaurus on steroids. It interfaces with MALLET, the Java-based classification & topic modeling tool. It is very well-supported and continues to be maintained. Moreover, Python is mature in & of itself. There are a host of Python “distributions/frameworks”. There are any number of supporting libraries/modules for interfacing with the Web, databases & indexes, the local file system, etc. Even more importantly for text mining (and natural language processing) techniques, Python is supported by a set of robust machine learning libraries/modules called scikit-learn. If the reader wants to write text mining or natural language processing applications, then Python is really the way to go.

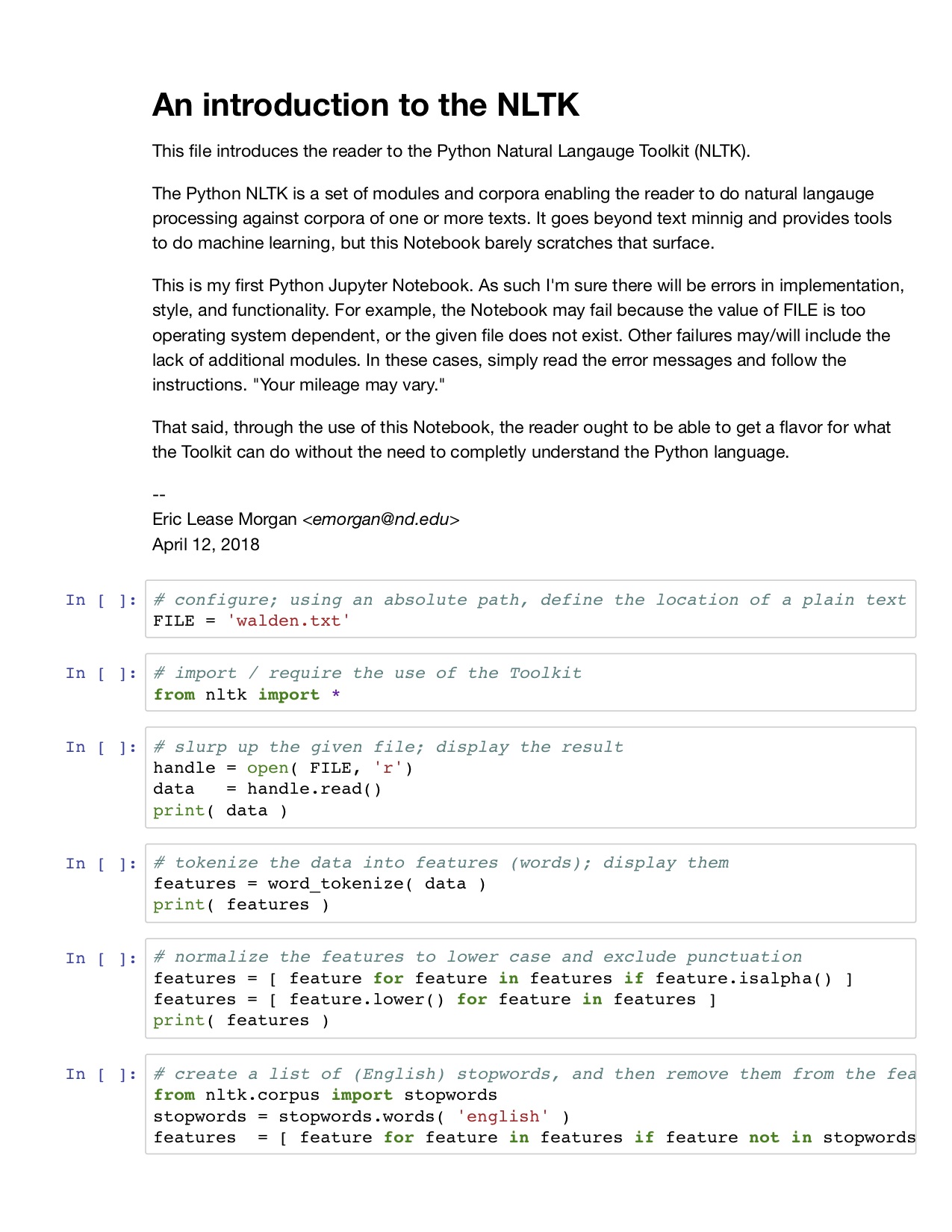

In the etc directory of this workshop’s distribution is a “Jupyter Notebook” named “An introduction to the NLTK.ipynb”. [1] Notebooks are sort of interactive Python interfaces. After installing Jupyter, the reader ought to be able to run the Notebook. This specific Notebook introduces the use of the NLTK. It walks you through the processes of reading a plain text file, parsing the file into words (“features”). Normalizing the words. Counting & tabulating the results. Graphically illustrating the results. Finding co-occurring words, words with similar meanings, and words in context. It also dabbles a bit into parts-of-speech and named entity extraction.

The heart of the Notebook’s code follows. Given a sane Python intallation, one can run this proram by saving it with a name like introduction.py, saving a file named walden.txt in the same directory, changing to the given directory, and then running the following command:

python introduction.py

The result ought to be a number of textual outputs in the terminal window as well as a few graphics.

Errors may occur, probably because other Python libraries/modules have not been installed. Follow the error messages’ instructions, and try again. Remember, “Your milage may vary.”

# configure; using an absolute path, define the location of a plain text file for analysis

FILE = 'walden.txt'

# import / require the use of the Toolkit

from nltk import *

# slurp up the given file; display the result

handle = open( FILE, 'r')

data = handle.read()

print( data )

# tokenize the data into features (words); display them

features = word_tokenize( data )

print( features )

# normalize the features to lower case and exclude punctuation

features = [ feature for feature in features if feature.isalpha() ]

features = [ feature.lower() for feature in features ]

print( features )

# create a list of (English) stopwords, and then remove them from the features

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

stopwords = stopwords.words( 'english' )

features = [ feature for feature in features if feature not in stopwords ]

# count & tabulate the features, and then plot the results -- season to taste

frequencies = FreqDist( features )

plot = frequencies.plot( 10 )

# create a list of unique words (hapaxes); display them

hapaxes = frequencies.hapaxes()

print( hapaxes )

# count & tabulate ngrams from the features -- season to taste; display some

ngrams = ngrams( features, 2 )

frequencies = FreqDist( ngrams )

frequencies.most_common( 10 )

# create a list each token's length, and plot the result; How many "long" words are there?

lengths = [ len( feature ) for feature in features ]

plot = FreqDist( lengths ).plot( 10 )

# initialize a stemmer, stem the features, count & tabulate, and output

from nltk.stem import PorterStemmer

stemmer = PorterStemmer()

stems = [ stemmer.stem( feature ) for feature in features ]

frequencies = FreqDist( stems )

frequencies.most_common( 10 )

# re-create the features and create a NLTK Text object, so other cool things can be done

features = word_tokenize( data )

text = Text( features )

# count & tabulate, again; list a given word -- season to taste

frequencies = FreqDist( text )

print( frequencies[ 'love' ] )

# do keyword-in-context searching against the text (concordancing)

print( text.concordance( 'love' ) )

# create a dispersion plot of given words

plot = text.dispersion_plot( [ 'love', 'war', 'man', 'god' ] )

# output the "most significant" bigrams, considering surrounding words (size of window) -- season to taste

text.collocations( num=10, window_size=4 )

# given a set of words, what words are nearby

text.common_contexts( [ 'love', 'war', 'man', 'god' ] )

# list the words (features) most associated with the given word

text.similar( 'love' )

# create a list of sentences, and display one -- season to taste

sentences = sent_tokenize( data )

sentence = sentences[ 14 ]

print( sentence )

# tokenize the sentence and parse it into parts-of-speech, all in one go

sentence = pos_tag( word_tokenize( sentence ) )

print( sentence )

# extract named enities from a sentence, and print the results

entities = ne_chunk( sentence )

print( entities )

# done

quit()

Links

- [0] Python Natural Language Toolkit – http://nltk.org

- [1] Jupyter – http://jupyter.org